Chromosome Comic, part I

The first of two deliveries on the exhibition Chromosome Comic or the Modern Prometheans, at Biquini Wax EPS, Mexico City (February-April, 2023)

Welcome back and hello to all those who are new here. Thank you for reading, sharing, and subscribing.

One of the big issues of a self-managed newsletter (formerly known as a blog post) is that it’s hard to set up limits: this delivery is so long I had to cut it in two. In this first of two parts I will discuss the exhibition Graphic Turn: Like The Ivy on the Wall at the MUAC in Mexico City, Mexican comics and Chromosome Comic or the Modern Prometheans, the exhibition I curated at Biquini Wax EPS in February 2023. Estimated reading time is 10 minutes. Enjoy!

-

A lot has happened since I last emailed you, the most exciting of which is that I opened two exhibitions: one in Mexico (Chromosome Comic or the Modern Prometheans, Biquini Wax EPS, Feb 3 - April 8) and one in Paris (AMEXICA, Institut culturel du Mexique, April 20 - June 15). AMEXICA has just been extended so you can now visit it until July 13th! if you are in town or know someone who will be, send them to this show of 13 brilliant contemporary Mexican artists whose works are present in the Servais Family Collection.

I’m dedicating this delivery of the newsletter to Chromosome Comic though, expanding on my initial email regarding the notoriety of graphic works and a shift in the kind of content and works in the latest documenta through the research collective Red de Conceptualismos del Sur.

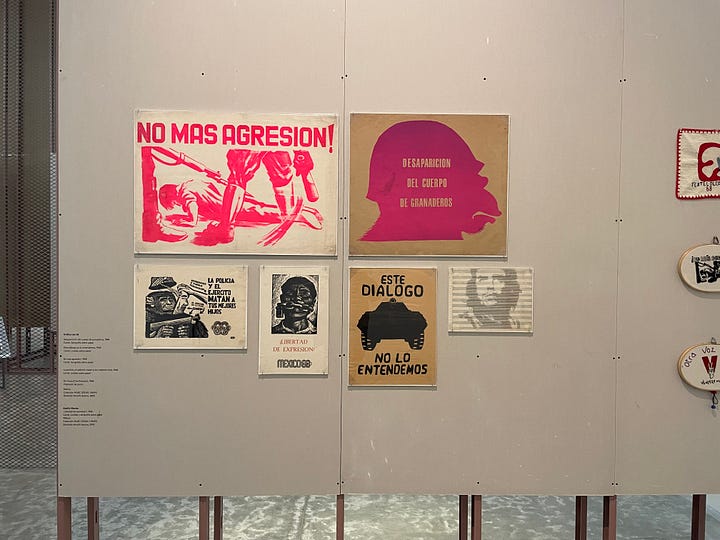

After that first email, Sol Henaro, curator of documentary collections at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City (MUAC) and one of the researchers from la Red, reached out and proposed that I come and tour the exhibition Giro Gráfico with her and part of the museum team in order to have a dialogue about all these topics. Lucky me! Giro Gráfico was the second major exhibition collectively authored by la Red after Losing the Human Form: A Seismic Image of the 1980s in Latin America (2012). Both exhibitions were initially presented at the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía, but Giro Gráfico is the first one that traveled to be presented, although in a reduced form, at the MUAC (it closed a couple weekends ago).

What a privilege to have this enlightening visit at the beginning of February in which Sol shared a behind-the-scenes view of the herculean process of researching, curating, and negotiating stories, concepts, and ways of orchestrating so many practices (mostly coming from contexts of activism) into a coherent exhibition within the very distinct program and mission of two major institutional museums, with as many as 50 researchers scattered throughout different time zones. The ongoing challenge of la Red is not only logistical but above all ontological, as their work is based on questioning the 'correct' ways of naming things (like visual practices) and established labels and categories, delving into the heart of existing historiographic narratives, which they regard with rigorous skepticism.

Touring the exhibition Graphic Turn, Like the Ivy on The Wall with Sol Henaro. The title of the show takes a line from a song by the Chilean musician, artist and militant Violeta Parra (1917-1967), Volver a los Diecisiete (1957)

As we have discussed, the controversies surrounding documenta stemmed as much from the exhibited practices as from the curatorial framework that allowed the inclusion of many artistically minded practices, but not necessarily “works of art”. This resonated strongly in Giro Gráfico, an exhibition that deliberately avoided discussing art or works of art, focusing instead on practices closely tied to struggles and forms of resistance that draw from visual cultures and, as part of their ongoing actions, produce powerful ’visual cries' that are often (but not necessarily) informed by artistic visual cultures. The act of including (and how to) the objects within the imposing walls of the museum always brought forth an active questioning of whether the museum co-opted, neutralized, or enhanced the works, seeking to establish a relationship of respect and care with the people and the objects as repositories of a strongly political memory that needs to be both preserved and kept alive.

These topics are at the core of ongoing debates on what is the role of the museum (and the role of curation) and what are the ways to achieve its shifting missions, which are going more and more towards the care of existing communities and less towards the establishing or maintaining of obsolete notions of universality (they are obsolete, you know? lol). We’ll keep coming back at this over and over and we just did as Annabela Tournon Zubieta, a researcher (who is also part of la Red de Conceptualismos del Sur) invited me recently (excuse me for bragging, she is actually an incredibly cool historian and curator) to present with her the catalogue of Grupo Mira, a counterhistory of the 1970s (the exhibition she curated at the Museo Amparo in Puebla and also at the MUAC in Mexico City), at the Institut Culturel du Mexique in Paris.

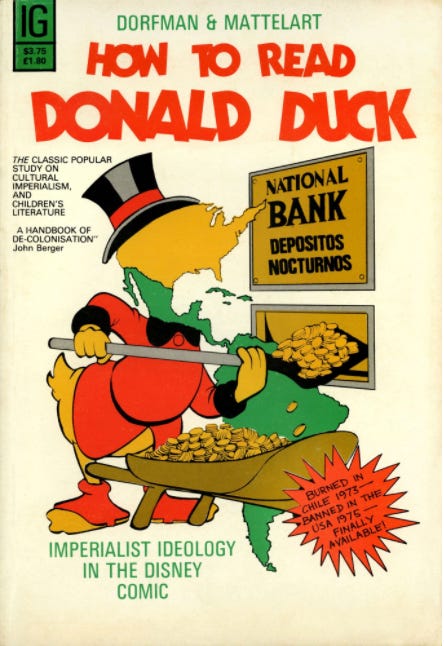

For this catalogue I wrote two brief essays focusing on the Grupo Mira’s use of comics, particularly under the light of dependency theory studies which were very influential during the group’s active time, between 1965 and 1982. More precisely, I elaborated on Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelard’s essential book How to read Donald Duck (1971), a critique to Disney comics with the background of the USA’s nefarious interventionist policies in Latin America, which infamously culminated in the coup d’etat that abruptly ended Salvador Allende’s socialist project in Chilli in 1973. Comics were from then on treated throughout the continent as unforgivable vehicles of ideological imperialism, which is honestly quite difficult to argue against because well… have you read this or other Disney comics??? Scrooge McDuck (known as Picsou in French or Rico McPato in Spanish -best name, obviously-), is actually pretty ghastly. If you haven’t read it please take my word for it and don’t just give it to any child you remotely care for, seriously it’s like the characters from Succession got together to write stories for children and teamed up with Disney to do the drawings. You don’t want children learning anything from them unless you are a billionaire trying to to establish a legendarily toxic empire of greed which will become the source material for future tabloids and screenwriters.

Dorfman and Mattelart’s How to Read Donald Duck (originally published in Spanish in 1971)

in the edition in English published by Seth Siegelaub's International General.

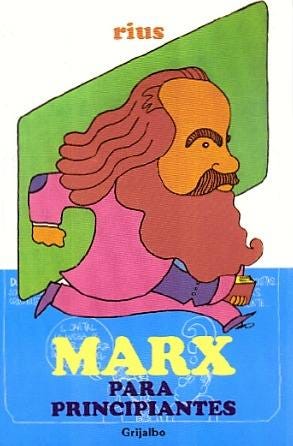

But anyway, in Mexico the future of comics studies and the perception of comics from academic circles was sealed even for people who did comics, like Eduardo del Río, Rius (1934-2017), one of Mexico’s most prolific comic artist who from the mid 60s onwards published political cartoons in books (so important, as opposed to disposable, materially fragile comics) detailing different aspects of the political spectrum focused on the dissemination of leftist ideas, and essentially using comics in the only way thought to make them morally and politically redeemable, which is as educational tools for the awakening of the masses. Rius did this while publicly disdaining historietas, which was the incredibly popular local form of comics in Mexico for most of the XXth century.

One of Rius’ best sellers, Marx for Beginners. Rius published many books about different figures from politics and ideologies.

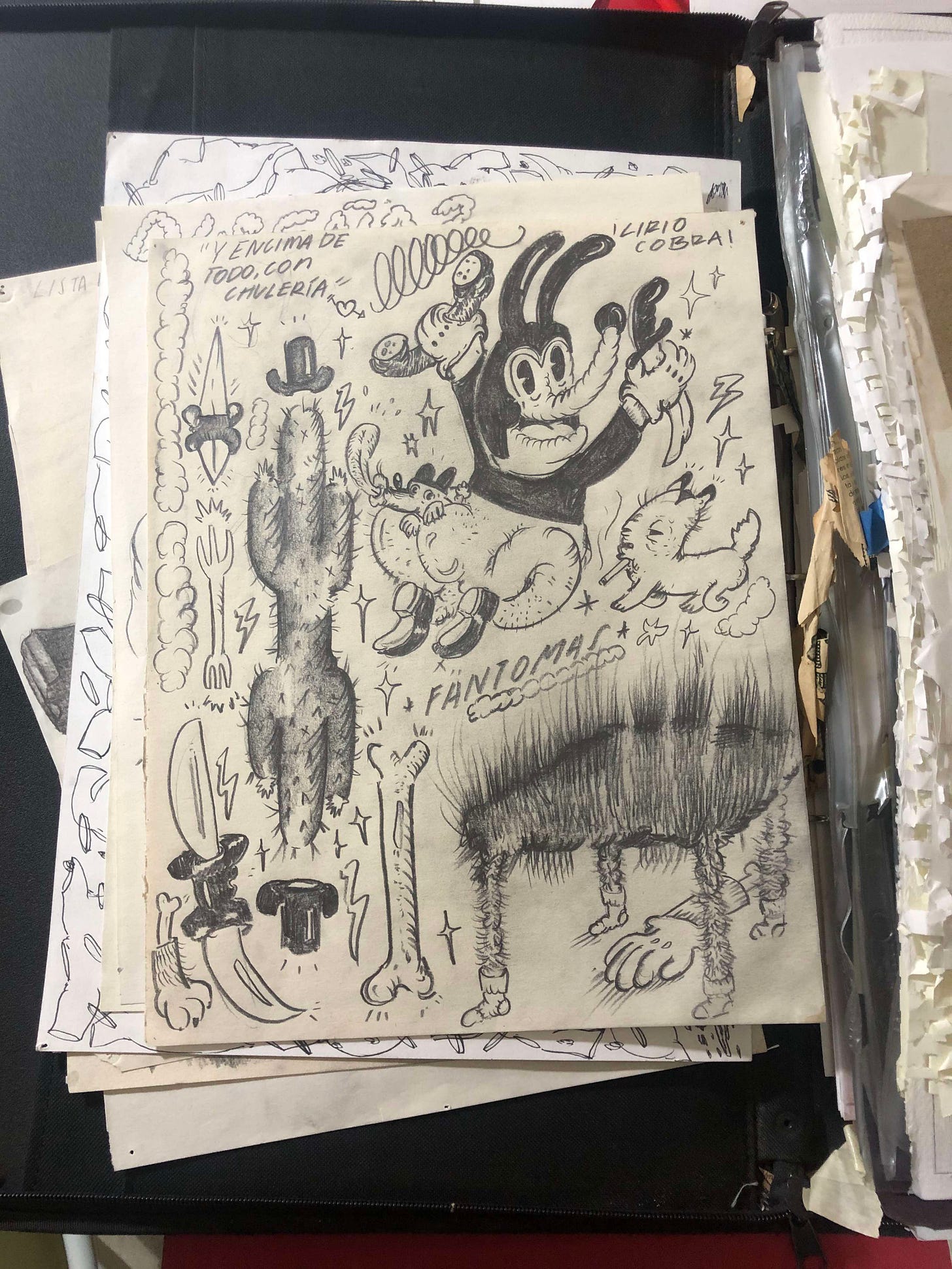

A figure that stands out in this context is that of Zalathiel Vargas (born in 1941) an artist who didn’t shy away from consistently using the visual language of comics in his paintings and works on paper, although Zalathiel’s references were clearly in the countercultural comics of the San Francisco scene of the 1960’s and 70’s that he would make dialogue with references coming from historical references in México.

A project for a mural by Zalathiel Vargas, undated, triptych of ink on paper, 28 x 21,2 cm each

The work of Abraham Cruzvillegas (born in 1968) and other artists from his generation come to mind as some of their first works were actually political cartoons imbued with all of these ideas, mixing politics, satire, social observation and self derision. In the case of Abraham I remember him recalling with hilarity how, after he assisted (with Damián Ortega and others) a course on cartoons imparted by El Fisgón (a famous political cartoonist who has become THE authority in the history of Mexican cartoons, writing several academical books and curating many shows about it in my favorite museum, El Museo del Estanquillo of Carlos Monsivais’ collection in Mexico City) he found himself not drawing monos but reading Nikolai Bukharin’s writings on revolutionary theory.

A drawing by Abraham Cruzvillegas, from around the time he was exploring political cartoons, courtesy of Abraham Cruzvillegas

-

Somehow we magically make it to the summer of 2020 and I’m home finishing a proposal for a writing residency in which I wanted to develop a project I had been working on since 2016 called Chromosome Comic. As I write the list of artists I wanted to cover on my texts I realize most are part of, or had been involved with, Biquini Wax EPS, an artist-run space originally founded in León Guanajuato by Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba (born in 1988), who later moved to Mexico City, bringing the space to the Colonia Escandón (they’ve had three locations in total) and housing there many young artists coming from other cities in the Mexican provinces, which is part of what makes this place so unique. That day I sent an email to the collective email of the house, telling them about my big DUH! moment, and how we should make Chromosome Comic happen together. It took us the following two and a half years of zoom sessions, emails, studio visits and failed applications for funding until Chromosome Comic finally saw the day on February, 2023.

The name is a play on the title of an exhibition by Daniel Guzman (born in 1965) called Chromosome Damage, in which he presented a series that epitomizes the kind of practices and approaches I’m interested in. Daniel first presented this series of works on paper in the Drawing Room in London in 2015, and as part of the show, there was a vitrine with several issues of the "vintage" Mexican historieta Hermelinda Linda. Initially, Hermelinda Linda was the story of a witch (the historieta was called Brujerías, Witchcrafts) who was so effective in her potions that, despite her incredible ugliness, had no trouble getting anything she wanted. As the comic gained popularity (and the attention of the government, who judged it inappropriate to feed the public's thirst for witchcraft), the title was changed to focus on the main witch, exaggerating the satire and doubling up the double entendre jokes and racy content. This was a comic for adults and certainly the kind of popular comic that Rius would have HATED.

Hermelinda Linda crushing some dirty hippies

Hermelinda Linda was supposedly made to be truly awful as you can see, but still she could bring any guy to his knees after using them as toys for her pleasure, and she could mock and laugh at anyone or anything, which is a paradox of liberation that we find in other Mexican comics of the time, in which female characters are portrayed (mostly by male editors, writers and artists) in a tone of satire or drama made to highlight their abjections (as social outcasts, promiscuous freaks, or as obese witches) which ironically allow them to attain a desirable degree of freedom and pleasure. Is it extrapolating too much if I imagine the underlying moral of these stories as “Better to be repressed but pretty than free and ugly, signed, The male gaze”?

Back at Daniel Guzman’s drawings, I somehow see all at this at play here. Look at it yourself:

The paper (papel estrasa, we use it in Mexico to wrap tortillas or to wrap street food), the colours, the movement, there is so much sensuality and so much filth and fun in these drawings, inspired by a randy 70s comic but also by prehispanic imagery and the baroquely violent, fiercely sensual goddesses of the Mexica cultures. The title of that first show in London was taken from a song by the experimental rock band Chrome, which is like that little piece of pineapple on top of a taco al pastor (i.e., the cherry on top if you are unfamiliar with Mexican delicacies), all this cacophonous mix and to name it the artist uses these words, Chromosome Damage, that have the effect of amplify it all with the resonance of punk guitars banging in the background.

This is the spirit of what I call the chromosome comic, leaping as a parasite onto Daniel's image for something that is intrinsically damaged within the very codification of a body. However, by its intrinsic broken nature, it is also freed from any obligation to perfection or, to get to where I'm going, any obligation to an established tradition.

Paloma Contreras Lomas (born in 1991) aka Lirio Cobra, you can guess from her drawings her childhood included a strong dose of unsupervised reading of underground comics. Photo from a studio visit (2022).

The artists in the exhibition Chromosome Comic are the inheritors of this raucous spirit, of this rebellious desire to find fine art in peluche and libidinous comics, to rewrite the history of art in foamy, to coat with all sorts of fluorescent plastics all the existing canons to make them their own.

The artists included in the show are definitely part of the most contemporary core, the youngest, of this generation inspired by the comics Rius and other cultural critics dismissed as mindless entertainment that turned poverty and ignorance into spectacle. Younger artists have a different way (and distance) of looking at these products with which they are willing to engage and interrogate, which is already a huge step forward. And of course, as they are all children of globalization, their references are wide and international. For example, Fabián Giovanni Guerrero (whose work wasn’t in this show), an artist from Cherán whose work mainly happens in painting and drawings, deals with mythologies, living rituals, and politics from his Purépecha culture while formally using visual references from the worlds of Japanese manga and animations.

But staying a little longer on the historietas, far from redeeming these objects that definitely profited from a kind of mexploitation, the artists complicate our regard towards them. Take the work of Irak Morales, for instance, who takes super raunchy images from these old historietas and uses them as branding elements for mezcal bottles which are sold as potentially disposable artistic objects. The gesture seems simple, and part of it comes from an aspect of Irak's work that is very social, that happens when it encounters others in festive, gregarious contexts. However, it is also something that, as an object, both amuses and challenges, making us laugh a little too awkwardly. Why is that, he seems to ask?

A bottle of Irak Morales’ Mezcal Pierdenalgas (untranslatable)

Half of the artworks from the exhibition were made in dialogue with this idea, inspired by the work of Mary Shelley, her novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Promethean (first published in 1818, when she was 20), but also by the personal circumstances surrounding the period while she was writing it. It was a time in her life intensely marked by birth, the tragic deaths of her sister, of her own children, and of people important to her family context, as well as the birth of science and industry as we know it, and the paradigm shifts that it provoked. The time frame of the novel is nine months and parenthood is a central theme in the book, the notion of responsibility towards our creations as humans, whether theoretical, conceptual or biological.

Another book that was central to the concept was Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (published in 1993), Scott McCloud’s bible on what comics are as language and how to read them formally. On part II of this post I will note the breaking down that McCloud does of the concept of the uncanny valley, linking it with the work the artist Elsa Louise Manceaux did for Chromosome Comic. Elsa’s work was indeed essential to the development of this show, so we will explore more her work and other works from the show more in detail.

If you are dying to see Chromosome Comic, you can see the visit I made in English for Independent Curators International’s Intensives in Action feature. The ICI was also fundamental to the project as they were part of it since I first came up with the idea for a Curatorial Intenive in Dakar. More on that on the next delivery of this newsletter. See you then!

✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽✌🏽