documenta fifteen: where art and life are one

a late review of ruangrupa's provocative documenta

Welcome to the first issue of my newsletter, dedicated to reviews and open questions on mostly contemporary art exhibitions and events, including occasional interviews and other fun stuff I might come up with. This time I’m writing about documenta fifteen. It took me a while to finish this text because I’ve been busy planning an upcoming show (and juggling with a million things of course, but who isn’t), Chromosome Comic, opening February 4th, 2023 at Biquini Wax EPS in Mexico City, I’ll tell you all about it next time. Remember to subscribe if somebody forwarded this to you, and thank you everyone who subscribed! This newsletter is free and will remain so.

A quick word before jumping to it. I’m assuming you know what documenta is because sadly I live in a bubble of relatively like-minded people for whom documenta is like the holy grail of conceptual consecration in contemporary art, so a quick intro: documenta is an institutional behemoth that started in 1955 while Germany was trying to come out of the dark ages of Nazism, and it happens every five years ever since, in their own words, documenta has established itself as an institution that goes far beyond a survey of what is currently happening, inviting the attention of the international art world every five years for this "museum of 100 days." The discourse and the dynamics of the discussion surrounding each documenta reflects and challenges the expectations of society about art.

Reading time is about 15 minutes.

Enjoy!!

_________

lumbung number one

At the entrance of Hubner Areal, one of the 32 official venues of documenta fifteen, a young woman speaks to a monument, tells it anecdotes, poses it questions. On a vertical screen several meters high, the woman wraps up her monologue by placing a tribute of curry wrapped on banana leaves on the footsteps of a monumental bronze statue of a male fighter and his adoring mother.

In another moment of the same work, Smashing Monuments by Sebastián Diaz Morales (2022), we follow a man’s strong legs crossing the streets of Jakarta, arriving to a monument in which a couple, that of a man and a woman, wave energetically on top of a dozen-meter high structure. Inaugurated in the late 60s, the statue was commissioned by Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, leader of the Indonesian liberation struggle against the Dutch colonialists who imprisoned him for a decade before he was liberated by invading Japanese forces during WWII. The image of curry wrapped in a neat package of banana leaves suddenly seems like a perfect metaphor for history: sticky, painfully spicy, with occasional sweet notes, maybe even hard to swallow, but impossible to isolate once you’ve mixed it.

“Perhaps you were meant to be built to only look to the future, only to see what is in front of you but not to see the things in the past,” the man in the video says to the couple as he pauses to light up a cigarette, “Just to let you know, right behind you, there are a whole bunch of skyscrapers competing to scratch the sky but of course they cannot, for the sky is too far for them to scratch. But at the same time, don’t worry. Behind you I see more than one Indonesian flags waving in front some of those buildings.”

The first venue I visited set the temperature of what was my experience of documenta fifteen, an event so massive in scale and so diverse in the expressions it presented that any single review claiming to have a general and definitive judgement on the entire thing came across as vacuously grandiloquent and ultimately tone-deaf, as what ruangrupa, the collective of artistic directors proposed, was to explode the notions of universality, singularity, individualism and commercialism. This was not another edition of the art world’s world fair, but as Diaz Morales’ work exemplified, an interpellation of history pulled to life with forceps by hundreds of artists, cultural workers and people from all walks of life involved in what the artistic directors called not documenta fifteen but lumbung number one.

documenta is now closed and if ruangrupa did anything right, it is in this time of processing a posteriori that we are to make sense of what happened for a hundred days in Kassel. The backlash ruangrupa received –well chronicled elsewhere– was so great that one has to take a pause and wonder about the impact of what a group of idealists brought to a part of the world’s attention, rubbing in many faces that the Global South is part of Europe’s history, past, present and future; that Europe is, as Franz Fanon said, literally the creation of Third World countries with all the claims to legitimacy (and sometimes a sense of revenge) that this phrase entails; that there are different ways of working, and most importantly, different goals when working, differing from any Western canons enshrined by art historians, museum bureaucrats, gallerists, curators and other artists; and most uncomfortably, that colonialism is alive around the world, so what is the role we are playing in all of this, you, me, us cultural workers? What is the role of art and artists in all of it?

What interests me mostly in writing this text is, on the one hand dwelling on a long-form review that I would typically read in other blogs (and my own blogs) before social media ate up the Internet. That is, a text that is not in a hurry or packed to be consumed in 7 seconds, one that is not afraid to present doubts and questions instead of just shouting an opinion or just benignly describing the historical elements that make up a work or an artist’s practice. On the other hand, this documenta felt really close to home as it touched on my long research on comics and art. If you know me, you know I’ve been carrying this for a long time and I recognise artists are getting somewhere with it in a way that feels very fresh, so I will try to make sense of different things I saw in preparation for an upcoming project and the next instalment of this newsletter. Before getting there, some thoughts on the concept that made everything happen.

Where art and life are one

You probably know by now that lumbung refers to a collectively managed rice barn. Almost three months after the closing of documenta I keep seeing expressions of this concept in other artistic projects where the notion of collectivisation is being implemented as a fundamental part of the process. Another field in which lumbung found fertile ground is that of literature, where the notion is being taken up to highlight the collective vs the individual, which can be refreshing in a field where the notion of the individual genius that creates solitarily has remain stubbornly healthy throughout time. An example of this is Relatos Lumbung, a book that has been edited in several languages in which seven writers outline ancestral traditions involving collective practices, highlighting the existing structures that could be helpful in healing “the current wounds that have their roots especially in colonialism, capitalism or patriarchal structures.” Another notable example is that of harvesting (jarvesting in Mexico) to which we’ll get to later.

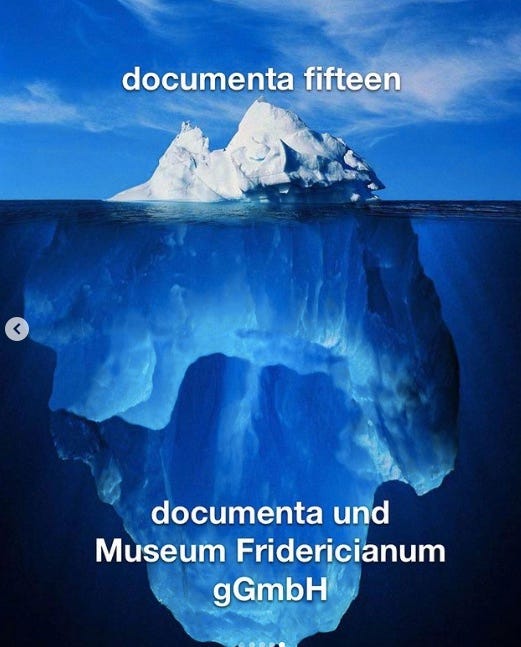

In documenta, lumbung acted as a metaphor, referring both to the practices of the 22 year-old ruangrupa in their own activities and to the methods they activated in the herculean task of developing a city-wide expression representative of the art world’s pulse, from their standpoint. As established by the group, lumbung was the conceptual silo from which everything flowed. Was the selection of ruangrupa to lead documenta at least in part strategical tokenism following the hegemonic art world’s incredibly recent awakening to the impossibility (and public backlash) of continuing excluding BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ communities, the collective and the Global South from everything? Regardless of ruangrupa’s prestige, for a German institution like documenta to choose them must have been regarded with a pinch of scepticism from the members of the Indonesian collective and others, and it clearly was. Upon being invited to develop a concept for the event, ruangrupa “invited documenta back, asking it to be part of our journey. We refuse[d] to be exploited by European, institutional agendas that are not ours to begin with.”[1] As Documenta accepted back, the process started.

The language used by ruangrupa in the handbook published for the occasion is remarkable in their consistent refusal to bow down to an institution that, in the hegemonic canon of contemporary art, is the throne for practitioners of conceptual art and those in their same orbit. “Collectivity”, as it would turn out to the chagrin of many apparently including the organisation of documenta itself, is not just a concept to work from, one that remotely brings to mind images of colleagues producing as a group the same objects, experiences, exhibitions and institutionally-friendly discourses (see “thought-provoking”) than that of individual artists. The results of working collectively are the sum of emotional, social and economical investments, and the result of a commitment that many individuals share for a common goal. That goal is rarely to produce objects (surprise surprise). People investing in working collectively gather to do something that is intrinsically difficult: to work in a group composed of people from different walks of life, many of whom are artists or artistically-minded, and discuss, dispute, convince, make decisions, and act upon them, trying to affect the world around them, beyond them, essentially doing political work from the fringes. documenta fifteen was a generous index of many such groups and the results of their work, some of which looked like art from a Western perspective, some of which didn’t look like art from a Western perspective, some of which was, indeed, not art at all but documentation or material witnesses to their processes, discussions, agreements and disagreements. Sometimes the art was there, sometimes the art was elsewhere, or it happened when you were not looking. What was most provocative (sometimes unbearably so) for many, was that documenta fifteen also acted as an index of the grievances that triggered the emergence of those groups, because such hard work is not undertaken for nothing (rarely only for money or prestige), but because the people that organise in this way are usually fed up, tired of waiting for governments to do their job whereas related to art institutions or any other necessity of society; tired of waiting for justice, tired of good intentions.

As expressed by ruangrupa, “most collectives in the lumbung inter-lokal come from contexts where the state had failed to support the development of infrastructure and a support system for art and culture,” and so the collectives and individuals invited embodied the notion that art is not an object, or only an experience, but part of a life lived with a purpose, or paraphrasing ruangrupa, those groups that embodied the point where art and life are one[2]. Was ruangrupa saying that the exclusive purpose of art should be political action? That all artist should be activists? That all art should be useful? That all Europeans should feel guilty for being born? Obviously they were not, although many people felt personally aggressed, offended or disappointed by what they felt was an edition ‘not artistic enough’, ‘historically and artistically lame’ or plainly going ‘against history’ (against their history, obviously), whatever that means.

ruangrupa certainly took the opportunity to show us, their 700,000 visitors, that both art and politics are umbrellas much larger than usually allowed, and that, (indulge me in the following metaphor) when you invite to the table people that have, for several hundred years, been watching the feast from the outside, contemplating under rain and snow while you eat that juicy steak (or your vegetarian option), they will come in, but they won’t eat under your terms, at your pace, or following your notion of manners. They may even change the terms of the party, and you can also be part of it, or get bitter because ‘things are not what they used to’. In other words, the attitude to enter documenta was one of openness for what was surely going to be a different edition of the event.

I dare say, most people growing up somewhere in the Global South is no stranger to collective practices. Living in a country where the government is expected to do its job (whether you may disagree on the quality of the outcomes or on specific policies) is abysmally different to living in one in which corruption and state-wide incompetence is taken for granted and is hence the structural basis of all civic life, regardless of your social status. In that sense, documenta as a state-funded platform for artistic practices is in itself a sample of Western privilege, one that was used to make a point and radically turned on its head by ruangrupa’s proposition.

El giro gráfico

From the many constructive comments colleagues had of documenta (there were many, but they were drowned by the German media hysteria), one that resonated with me was that ruangrupa could have been more generous in connecting the practices they presented (many of which have no visibility in the West) to artists better known in places like Paris or London (better known there, not from there, that’s were the comments came from), which would ideally result in the establishment of a bridge between these practices or a clear network of practices. So much could be argued from this sentence alone (“why is it my job to enrich the historical perspective of the hegemony?, “Is there ever a time in which the South stops enriching the North?”, “There is not one art history established by the North that needs ‘enriching’ with snippets from the South”, “Do they really think they still are the center from which things irradiate?”, “Do they really still believe in A history of art?”, etc.) but I think we can agree that this role of connecting the nodes of artistic sparks happening around the world is indeed one of the most important roles of curation, a field in which we strive to render these links visible so our understanding of the human experience becomes larger, not more insular.

From the connections I noticed, I will unpack here one between the work of ruangrupa and that of the research group Red de Conceptualismos del Sur, which defines itself like an affective, activist network that, from a plural South-South position, seeks to act in the field of epistemological, artistic and political disputes of the present.[3] As in the case of ruangrupa, la Red emphasizes the experiential aspect of cultural and artistic work, one that goes beyond the field of art and its aimed at understanding the historical frameworks in which the presents operate in order to directly affect them.

Integrated by historians, curators, artists, and activists, la Red is responsible for two crucial exhibitions. The first one, Perder la forma humana, una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Losing the Human Form, A Seismic Image of the, 1980s in Latin America), was presented between 2012 and 2014, starting at the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía in Madrid and culminating in the Museo de la Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, in Buenos Aires. This show brought together “episodes as dissimilar as the creative strategies employed by human rights movements to make visible the disappeared and victims of State terrorism [in the Latin America of the 1980s], the survival of the Arete Guasu ritual in the Paraguayan Chaco, the practices of poetry, theatre, music, comic strips, architecture and graphic activism collectives in the dispute over public space in the midst of repression, the experiences of sexual disobedience, and the parties and performances in underground spaces in different countries of the continent.”[4] Many similarities between the scope of la Red and that of ruangrupa are evident. The most essential is that the interest of both collectives lays in the ongoing history/stories of human action, suffering and rebellion against violence and oppression and the way these rebellions make use of artistic languages or strategies, not in the artistic practices and their genealogy per se. The point in which the work of ruangrupa and la Red intersect most strongly for me is that of the graphic action (acción gráfica), or as outlined in that first exhibition, the common use by many collectives of silkscreening and graphic art as a privileged political tool and, with it, the deployment of renewed forms of graphic action as a different form of socialization of art.[5]

This surge of the graphic form and all its potentiality was further developed in the exhibition Giro Gráfico, como en el muro la hiedra (Graphic Turn, Like the Ivy on the Wall) currently in its second itinerancy at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City after being inaugurated at the Reina Sofía in May 2022.

As expressed by Ana Longoni and Sol Henaro in a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition, the show is not concerned with the distinction of whether the objects presented are art or not, but in the ways the actions take elements from visual, artistic and creative languages with visual grammars to create poster banners, documentation of actions in the street, embroideries, fanzines and other forms with precarious and diverse materialities which eventually accompany actions or are civic action. For Longoni, certain works are not art but the sign of a mode of collective and street action that bring up the way in which these objects and the memory they enclose are preserved, exhibited and activated in the museum when they are not active in the streets.

The breaking of this barrier of distinction (and the way it questions the museum’s purpose in itself, i.e. ‘why is this object in the museum alongside contemporary art?’ There is a shifting definition of the museum embodied in these kind of presentations, both those of la Red and that of ruangrupa) is allowing both La Red and ruangrupa to bring into exhibition spaces graphic practices such as silk-screening, the recovery of typographic and printing processes for the creation of banners, and, most importantly for me, the production of comics, fanzines and other rebellious graphic literatures that have been historically relegated to the margins, from which wonderful works have been created, destroyed and forgotten.

Another point of convergence between both collectives, one that further validates ephemeral, quick-response and informal ways of publishing like those typically associated with comics and zines, is that both collectives try to grasp the present. Even if the work of la Red has a fundamental archival element, both teams strive to work, being affected by and affect what is happening now. In the case of la Red, the way of expressing this in the exhibition space becomes the Agora of the present and the Biblioteca Cuir (pronounced queer), an unguarded space in which publications (including comics, zines, pamphlets, etc) are available, and are constantly being replenished as resources. One equivalent of this in documenta fifteen (there are several, can’t describe them all) was of course the Lumbung press and the notion of harvesting that I mentioned before. The Lumbung press, ran by Erik Beltrán in Kassel, publicly produced many publications during the time of the exhibition, reacting in real time and with urgency to the lively, intellectually exciting and often dramatic everyday life of the lumbung.

Harvest refers to artistic recordings of discussions and meetings. Harvesters listen, reflect, and depict this process from their own perspectives, forms and artistic practices. Harvest can be humorous, poetic, or candid. They can take the shape of a sticky note, a written history, drawing, film, sound piece, or meme.[6]

The agora of the present and the idea of keeping track of what is happening today is as essential to la Red as harvesting is (because it’s still going on) for ruangrupa’s lumbung, who recruited many artists to take all kinds of notes during the time of the exhibition and feed them into a common pot of knowledge that took many forms, insisting with these actions that the process of sharing and building knowledge is part of the artistic experience, an artistic object whether it eventually becomes an artwork or not.

Organize, educate and agitate

No other artist or collective embodied all these junctions, crossroads and contradictions with such virtuosity, abundance and awe-producing rebellious punk-rock energy than the Indonesian collective Taring Padi, presented in three venues throughout Kassel, the biggest of which (Hallenblad Ost) showed a retrospective of the 24 year old collective. I don’t want to fall into the rabbit hole of controversies surrounding their presentation, which I think were overblown and used both by the extreme right and the click-hungry German medias to flatten the critiques implicit in all of their work and the overall radicalism of ruangrupa. Moving on, Taring Padi’s work was a revelation and I was thankful to be in its presence as it happens when you are in a truly inspiring exhibition that surprises and uplifts you.

It’s worth remembering how I first saw their work.

I travelled by train on a Saturday night, leaving work in Paris at around 6 and arriving at Kassel at 3 in the morning to meet my crazy friends of Tropical Tap Water, a team of artists-musicians participating in documenta fifteen as harvesters, with whom I shared a room that half-night. The next morning, while they were still sleeping after a night out, I took off silently around 9, opening the door of the Hotel Excelsior into the foggy morning of concrete buildings and deserted streets of Kassel. I grabbed a tea at the only place I found open at the Scheidemannplatz, a square where many tram lines converge, and started walking towards the East side of town, were I wanted to start the day following a friend’s recommendation to begin from the outside and end with what is traditionally the central home of documenta, the Fridericianum. It was an overall good call.

I walked in almost absolute loneliness for about forty minutes, crossing a highway, then a bridge over the river Fulda which divides the city in East and West, just encountering a couple teenagers in the ever surprising, uniquely-German spectacle of standing on a deserted street with no cars on sight, waiting for the pedestrians traffic light to turn green. I abode by the local rules (is it still a rule, though?[7]), telling myself that an occasional lesson in absurd patience is positive for the mind. I wasn’t in a rush anyway as all venues opened at 10. In the distance, a patch of green trees finally became visible, and as I approached it, an explosion of colours and drawings appeared on its patchy lawn, still fresh with morning dew. Dozens of corrugated cardboard banners, perhaps used during manifestations as catchy props with caricatured versions of state censors, dictators, modern-slave holders, invaders and all kinds of enemies of the people graced the entrance of the Hallenblad Ost, a former public pool. The banners were all unique and vibrant, all outside for everyone to see even if that made them vulnerable; unguarded, planted on the lawn, approachable, they were protected only by the respect of the locals and the visitors. This resonated with what Jiradej Meemalai of the Baan Noorg collective (that occupied a major space at the documenta Halle) from Thailand said on his visit to Paris before the summer, describing the collective’s experience with the locals as very positive, something that didn’t get to the headlines.

ruangrupa, like la Red de Conceptualismos del Sur before, went past the question of whether these objects were art or not. Loaded with intensity, these objects and others inside that venue screamed from the walls, demanding we don’t look past their use and isolate them as works of art, asking us to not depoliticize their message rendered in beautiful, complex, giant narrative epics with thousands of characters reminiscent in message and ambition to works from the Muralist period but also to the kind of hyper pop baroque produced by many contemporary artists that privilege an obsessive practice of drawing as the primary matrix of their work.

This question of whether these objects were art or not seems so irrelevant now, and that in itself feels quite significant. Are we really beyond this question? Has the gate been finally open? And what does that mean, symbolically and materially? These are questions to think about and perhaps discuss publicly, which we’ll do in February as the exhibition Chromosome Comic will open at the artist-run space Biquini Wax on February 4th. The next issue of this nascent newsletter will give these questions a genealogical background.

Wrapping it up

Wow, this is been so long and I haven’t got through half my notes, but if you got here, THANK YOUUUUUUUUUUUUUU. I’ll continue writing reviews and commentary to exhibitions and events I have the great privilege of attending or make happen with other friends, trying to publicly make sense on things and just trying to write more, which together with editing are my true passions. Speaking of which, I wrote this text in English and it hasn’t been edited, so thank you again for keeping up with typos, mistakes, over-complicated phrases and lame grammar.

See you next time and happy New Year if that’s your thing!!,

Cheers,

M

[1] Ruangrupa and Artistic team et al. (2022) Documenta Fifteen Handbook, p. 12

[2] Ibid, p. 24

[3] Clara Albinati, et al. (2022) Giro gráfico, como en el muro la hiedra, p. 16

[4] Amigo Cerisola, R. et al. (2012) Perder la forma humana : una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina, p. 11

[5] Ibid. P. 23

[6] Ruangrupa and Artistic team et al. (2022) Documenta Fifteen Handbook, p. 44

[7] Would Germans Ever Cross the Street on a Red Light?, https://www.wsj.com/articles/would-germans-ever-cross-the-street-on-a-red-light-1445907439

Hacemos una cita para febrero? Definitivamente me encantaría continuar esta conversación ya sea nosotrxs solamente o mejor aún, con otrxs. Abrazo