Jimmie Durham: This note should explain everything

On Jimmie Durham's retrospective, Humanity Is Not a Completed Project at the Museo Madre in Naples, curated by Kathryn Weir

Hello friends, welcome again to my newsletter, dedicated this time to Jimmie Durham’s retrospective Humanity is Not a Completed Project, curated by Kathryn Weir and presented at the Museo Madre in Naples (Dec, 2022- May, 2023).

I was very privileged not only to visit this show on its last weekend, to meet Maria Thereza Alves (a Brazilian artist and life partner of Jimmie) but also to meet there Kathryn Weir, who kindly walked me through the show.

This text was originally published in Spanish in the July edition of the literary magazine Letras Libres in Mexico with a SINGLE image! Here is the text in English (my translation) with more to look at. I decided to focus more on Jimmie’s and Maria Thereza’s passage through Mexico instead but if you are interested, Barry Schwabsky did a great review of this same show where he explained the context dispassionately. He finished his text by saying, “whatever we decide to call him, “Humanity is not a completed project” showed that, even if Durham never managed either to shed or to credibly claim a specific identity, he was one of the most remarkable sculptors of our time.” Let’s agree on that, or fight over it with a duel, it’s up to you.

As ever, all your comments and suggestions are welcomed and appreciated. Reading time is about 10 minutes.

Cheers!

_

Voices, echos and chimes lead to Jimmie Durham's retrospective at the Museo Madre in Naples, Humanity is Not a Completed Project, the first since the artist's death in 2021 at age 81.

In the first one, Durham addresses the visitor from a sizable flat screen situated near the building's entrance—a component of the 13th-century Palazzo Donnaregina. Seated before the camera or positioned at podiums globally, the artist, poet, and activist—now elderly—shares anecdotes and relativizes certainties. Speaking slowly,he constructs phrases reminiscent of aphorisms accompanied by gentle laughter, like an educator concluding lessons with humor to etch them into the listener's memory. At one point, he tells us that, when he lived in Mexico (between 1989 and 1993) with fellow artist, activist and life partner Maria Thereza Alves, they had to go to the station to take the bus to Cuernavaca, "and there was a security post there, an arch that was really useless, but we all had to go through it and pretend it was good for something, pretend that the security guard was also good for something. And I thought, this is a genius work of art!… it's the same thing with the Arc de Triomphe in France... official history is always silly, especially history that has these kind of silly lies," he says, and laughs.

A few meters ahead, at the foot of the stairs of the palazzo in the part built in the 19th century and renovated by Alvaro Siza in 2005, a monitor in the shape of a black cube shows the artist seated. From a table to his left he picks up a piece of wood with two ringbells between which he shakes a screwdriver, producing the exact sound of an old telephone ring (The Telephone Call, 2006). He puts the tool aside and picks up the receiver of a black telephone from the floor, "Hello?... No, I don't know anything about that, he just told me to pick up the phone and pretend to talk to someone...", quickly the conversation transforms from absurd to tense, his expression hardens, "Don't say that... why would you say that? ... I'm going to have to hang up...", he puts the receiver in his lap and while he takes a deep breath we want to know more of this two-minute melodrama where the artist shows us that it doesn't take great staging to awaken our thirst for morbidity and credulity, even if we know very well that it's all a lie.

The ringing follows us as we climb the stairs of the building, crossing on our way one of Durham's poems printed on the wall, "I want my words to be as eloquent as the sound of a rattlesnake..." rrrrring, rrrrring! This architecture, at once ancient and super contemporary, of soaring ceilings, basalt slabs, white marble and ironwork in the heart of this sedimentary city where every stone has something to say about the past, are as a whole the perfect introduction to this exhibition, and its curator, Kathryn Weir, knows it.

The last exhibition in her three-year term as director of the museum, Humanity is not a completed project is both the title of a work by Durham and a farewell phrase for Weir, who in her time at the institution installed a programme that for the first time tackled the interconnections between colonialism and fascism, between art and power through little-known stories set in Naples during Mussolini's pre-war regime (Beauty and terror: Sites of Colonialism and Fascism, 2022); the origins from the local Italian context and the acceleration of the climate crisis (Rethinking Nature, 2021-22); or the relativisation of the concept of progress and the dystopias it produces, recognising in Naples similar dynamics to those in other southern regions and countries of the global South (Utopia and dystopia: the myth of progress seen from the South, 2021-22).

These are all themes of intense concern to Durham, who in the 1960s and 1970s was a full-time activist in the American Indian civil rights movements in the United States, while drawing on aspects of his Cherokee heritage to comment in his work on the dangers of taxonomising a culture, transforming it from living matter to postcard pastiche or, perhaps worse, identity requirement. If the retrospective avoids a strictly chronological survey in favour of a series of conceptual and formal constellations, some key works and assemblages locate the thinking of an artist who foresaw the current debates around identity, perhaps without fully grasping the polarising proportions they would take on, particularly in the United States.

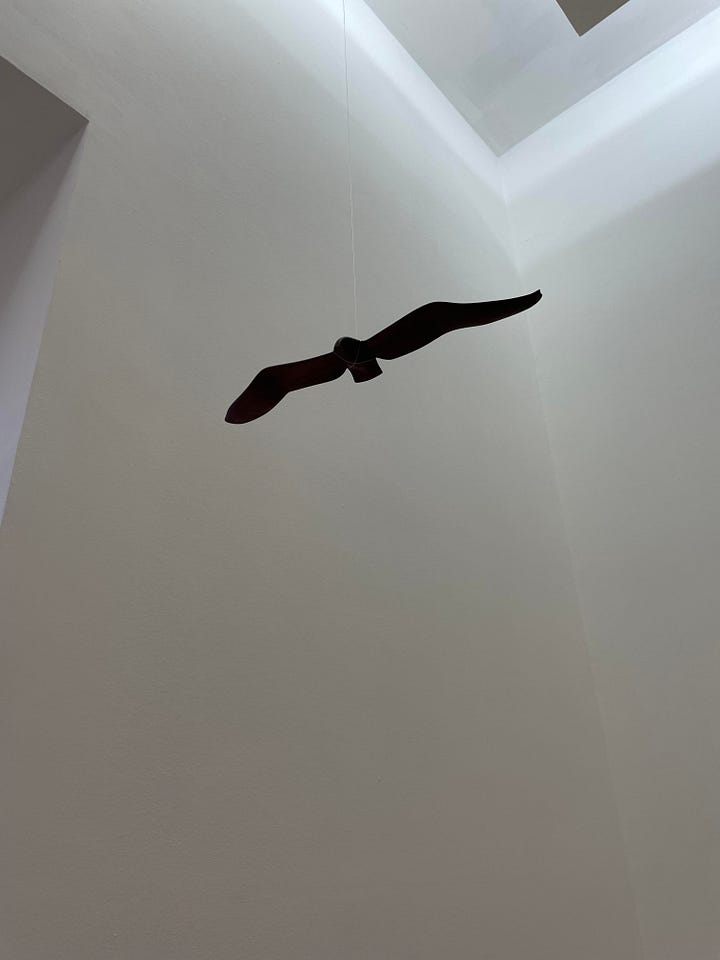

From one of these sets, perhaps the one that groups together the works in which Durham allowed himself to be most didactic (Museum of European normality, 2018, in collaboration with Maria Thereza Alves, or The Indian Family, 1985), a long horizontal panel never before presented stands out, God's own drunks from 1974, part of the work and visual thesis with which Durham graduated from the School of Fine Arts in Genoa in 1973. In it, the artist visually traces with photographs and drawings - adding informative, poetic and satirical commentary - the history of the flattening of Swiss folklore, a complex expression of the syncretism of the ancient pagan, Christian and Germanic rites of the Alpine region, which by the 1970s were already a product of banal consumption. The mirror effect is as eloquent as the rattle: the destruction of cultural wealth is not exclusive to exotic and unknown Indian peoples, he seems to be warning. In the same room, a small wooden sculpture of a hawk in flight made by Durham at the age of 14 (Nighthawk, 1954), completes an early portrait of an artist and the interests he would explore in an indefinable trajectory, dominated by the intensity of his sculptural work.

Different clusters show it in all its brilliance, from the third room in which, with a modest archival photograph, the curator recalls the arrangement of a dense group of works in the historical exhibition Original Re-Runs, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London (1994), from which she displays Armadillo (1991), A dead deer (1986), and Racoon (skunk) (1989), among other sculptures in which Durham mounts the skulls of different animals on connoted elements of urban control such as New York police cars or wooden beams of different thicknesses, origins and periods, lifting the animal from the earth and taking it to heights closer to the human scale while not humanising them, but rather turning them into mystical apparitions, still wild and untamable, enveloped in unexpected textures and materials that never cease to be what they are and at the same time become part of the works.

It is a constant notion in Durham's work, this almost animistic approach to materials, whatever their origin, natural or industrial. Of this, the sculptures Malinche (1988-1992) and Cortez (sic) (1991-1992) are paradigmatic examples. Malinche has a history of its own, illustrative of the wandering life of an artist who felt, in his own words, both an immigrant and a refugee who sought happiness outside the United States in Genoa, Cuernavaca, Berlin and Naples. According to Maria Thereza Alves, Mexico was the country where they felt best, surrounded by indigenous cultures that, in their evident abundance, could not be hidden. It is probably this encounter with Mexico that decided Durham to change the identity and form of the sculpture he initially presented as Pocahontas in the exhibition Pocahontas and the Little Carpenter (Matt's Gallery, London, 1988), and which has appeared since 1992 as Malinche (1988-1992). The woman's body, previously suggested by a high chair and a long dark-coloured robe, is now clearly depicted: if in Pocahontas it was abstract but majestic, in Malinche it is explicit but vulnerable. Her wooden arms culminate in slender hands that hold a white canvas covering her sex and legs, white-clad up to her ankles and beyond that one tiny, naked, human foot. The other, huge and wild, is made of agave leaves that might as well be tobacco leaves. From her hunched back suggested by a trunk hangs a golden bra. Shame torments the face of the reptilian-woman hybrid with eyes that stare at us, trapped between her world and our inquisitive imagination. In the artist's own words, the myth of Pocahontas and John Smith became an important operant in the construction of America and we find its counterparts throughout the hemisphere. In Brazil, the story is told of a woman named Iragema; in Mexico, Malinche.

According to Durham's instructions, Cortez is always placed in an adjoining room, with Malinche's back to him. Another work from his Morelos period when they lived, according to Olivier Debroise, in a house made of stairs, opposite the Salto de San Antón, Cortez is the emotional antithesis of Malinche, for he remains emotional even though his whole body has the aura of a bazooka. His blue eyes gaze towards the horizon, beyond us. The grimace of his mouth and the rictus of his face speak the cold language of the metals that surround his skull and give shape to his body, like a cyborg that needs pulleys, screws and steel hinges to move because it is nothing without the technology that anchors it in the human space; his whole body is a weapon, its barrels are in his head and triplicated in his penis. As the only symptom of humanity, his left arm looks like a prosthesis covered with a disturbing skin that ends in a hand covered with an inert glove.

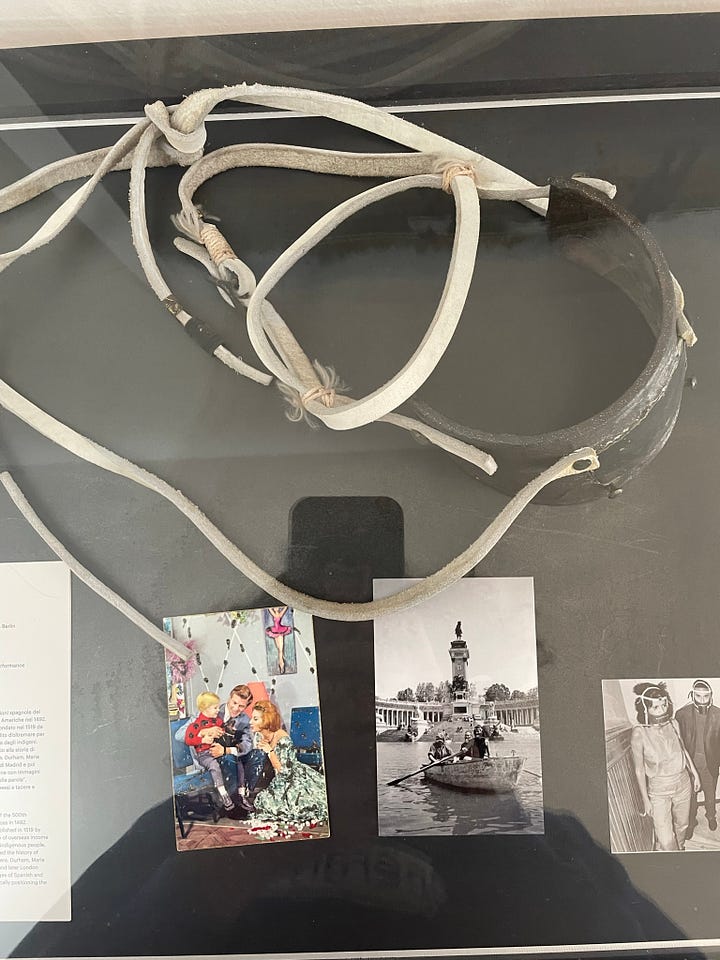

Admittedly, the colonisation of America is constantly in Durham's imagination during his time in Mexico, where he lived but where he exhibited only once in the show Si Colón supiera..., curated by Rina Epelstein and Olivier Debroise at the Museo de Monterrey in 1992, the year of the much disputed celebrations for the fifth centenary of the discovery and evangelisation of America, as it was called at the time. Later in the exhibition we return to this emblematic year in the documentation of the performance Virginia/Veracruz performed in the streets of Madrid by Durham and Maria Thereza Alves with the participation of Alan Michaelson. In the action, the three wear a leather muzzle that covers their mouths but also holds their heads with ribbons that press against their foreheads a series of photographs and postcards with images reproducing the supposed ideal of the family (white, heterosexual, middle class) and other social impositions against which the artists find themselves symbolically silenced. Armed, or rather, thus unarmed, they walk the streets of Spain and England, visiting the monuments of the imperial powers. The work recalls that of another duo, that of Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña, who in Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992-1993) took the idea to an extreme register, painfully illustrating the reality faced by the original peoples. The duo was exhibited locked in a cage in different contexts, between museums and squares in Europe and the United States, awakening in a non-anecdotal part of the public the entire repertoire of racist reactions by using the same codes (albeit satirised) of human zoos.

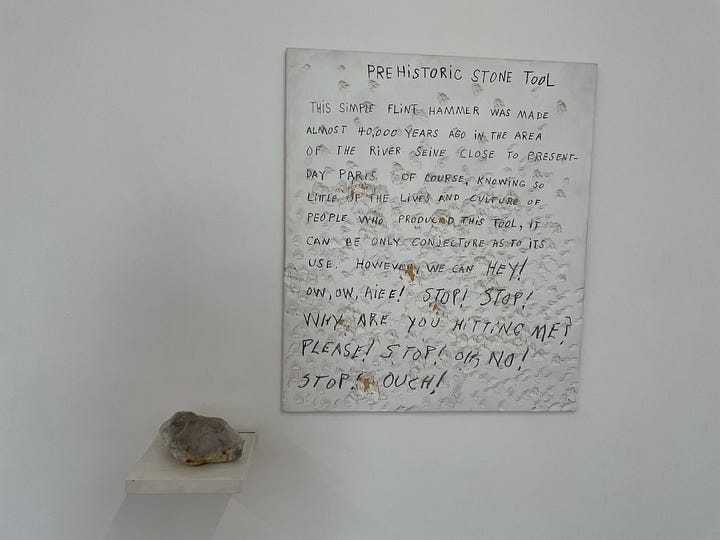

The digestion of these colonisations never left Durham's work, but it did transform over time, becoming increasingly granular, porous to the artist's curiosity about the singularities of science, history and its inseparable relationship with the word; with architecture and its most fundamental elements, such as stones, themes with which the curator composes different formal landscapes throughout the exhibition that often remind us of the artist's sense of humour, allowing us to approach the work and the person at the same time.

In one of these groupings dedicated to architecture we find a reference to the arch Jimmie spoke of in the first prelude, to that silly lie of history that he decided to appropriate, creating a series of triumphal arches for personal use with dissimilar materials (Arc de Triomphe for personal use (red), 2007), perhaps drawing our attention to the fact that history belongs to whoever has the budget to create lasting monuments to imaginary victories.

Another, at once touching, profound and magically absurd, brings us closer to the end of the exhibition by showing the last work Durham left on the workbench in his studio in Naples, a few steps from the museum: the enormous bronze cast skull of a turtle (Cast turtle head (unfinished work in progress), 2021), like an aged version of his most impressive sculptures. In front of it, a series of wooden panels accumulate names printed, painted or engraved in different materials under a small plaque that with an air of officialdom announces "The names of the team of scientists who submitted an article on the human chromosome 14 in Nature magazine" (2003); and to one side, as if breaking with the gravity of the whole, a sculpture made up of a series of assembled tubes, dressed in a black shirt fused to the surface of the plastic and topped at the bottom with the handwritten phrase "This note should explain everything" (1996).

The nearby words of the artist underline what interested him in science, not the colonisation of subjects and fields, but the opening of new possibilities for a different future: “My work is based on the idea of science as curiosity, as a new way of looking at things, on research without preconception that leads to change and innovation. That's what science means to me: a lack of predefined ideas, the acceptance of discovery, an unexpected view of reality."

In the distance, the sound of the phone rings louder with each step, mingling at times with the artist's voice coming from a speaker as he recites one of his mesmerizing poems, filling the space with an intensity that owes nothing to the rattle of the snake.

rrrrrrrrring!