In the artist's words: Viktoria Oreshko

A visit to the painter Viktoria Oreshko (Ukraine, 1997) at her atelier, inside the school of Beaux-Arts de Paris

Dear friends,

Welcome to the new year! In 2024 I am inaugurating a section called ‘In the artist’s words’ which started after I visited the studio of Viktoria Oreshko (Ukraine, 1997) at the School of Beaux-arts de Paris. Like any good studio visit, the conversation we had then was a stimulating window into the artist’s mind, her personal history and motivations, obsessions and technical methods.

That evening after I left her, I took refuge from the rain in a café where I hastily transcribed from memory most of what you’ll read, reacting to a feeling of urgency I had after our encounter.

I leave the rest to Viktoria, who strings together the heart-shaped pearls of art, history and her own story in this studio visit, told in her own words.

Until February,

m

-

I was born in Sarny, Ukraine in 1997 and there I went to an art school with a solely academic approach to the subject I studied – monumental painting. Our teachers were inheritors of Soviet traditions, where painting was a technical craft best expressed through the representation of anatomically perfect bodies in non-existent grand projects. I learned many techniques like fresco or mosaic and went through a good school of life, but once graduated, it was difficult to detach from this academic approach and from its idol – the human body.

The aftermath of this experience is present in my work in different ways. I was running from it so badly but ironically, I currently work with the body, though now it’s not the same thing.

While the occupation of Ukraine by the Soviet Union ended in 1991, it has taken my country some years to overcome the kind of totalitarian thinking that occupiers wanted us to inherit and that became our normal way of life. This is subject I also research in my work, more precisely growing up as a woman in a society traumatized by soviet communism.

For example, when I was little, there was one day a month when babies brought by their parent to daycare had to line up, so monitors would check their nails. If for whatever arbitrary reason, their parents hadn’t cut the baby’s nails as expected, the monitors would cut them cruelly, close to the skin, expecting to draw blood from our little fingers. I don’t consider myself a victim, but that’s how life was, it was an experience of casual violence reproduced by people who were educated in an even more cruel soviet system.

The beginning of a full-scale invasion in Ukraine was a turning point in my life. Living in Paris, I had to deal with the fact that all my family stayed in Ukraine and that somehow I needed to continue to work and exist as an artist. Honestly, the life I had in France lost all meaning in a second. I couldn’t paint for two months, and it was so difficult to start again. Painting seemed such a useless thing to do because the only thing that made sense was to fight on the battlefield or to help others to fight. But as an artist, the full-scale war made me break with my academic limits and I learned to use painting for the first time to explore and express something I don’t know how to cope with otherwise, and try to discover it through my work.

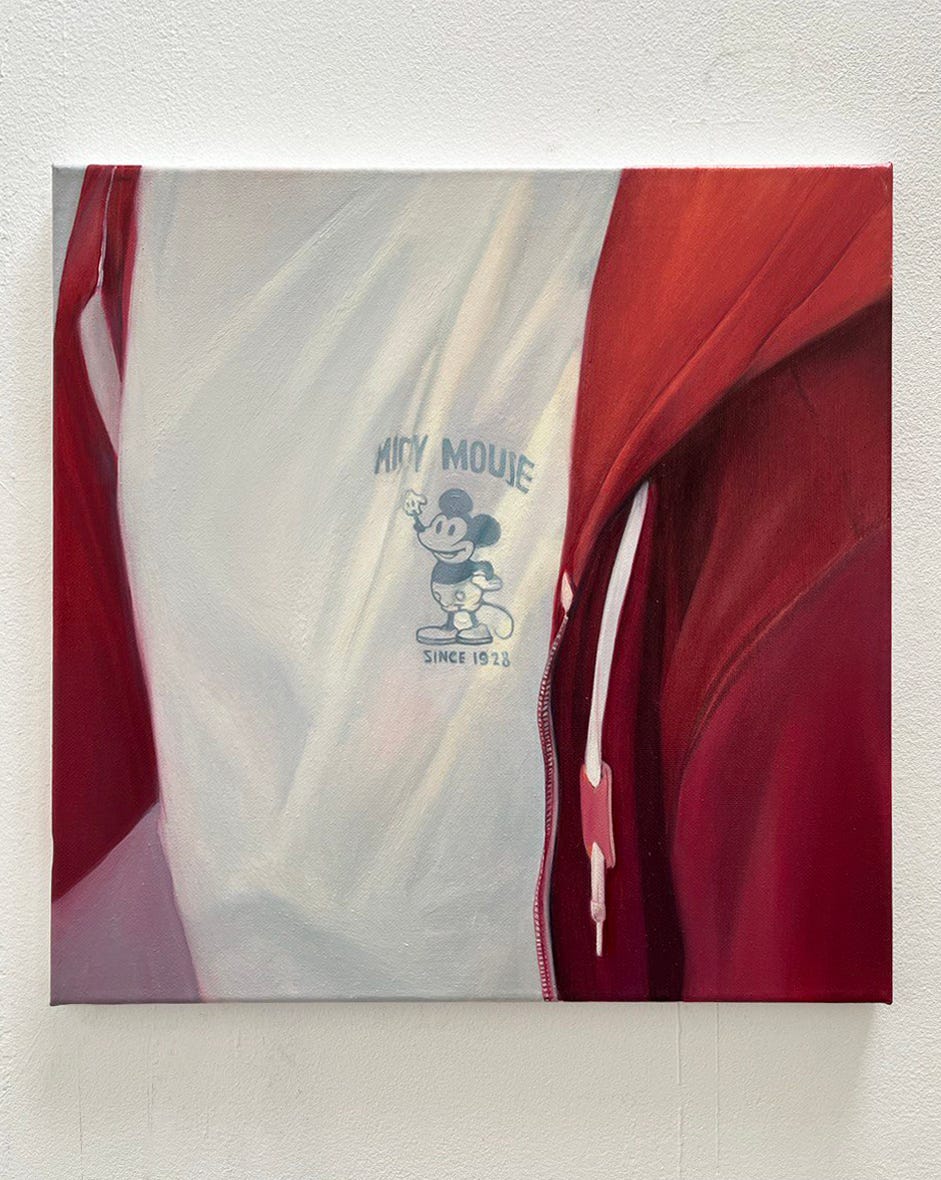

At first, I did two large works, semi-blurry close-ups of children in which what pulls you in is their clothes, the cheerful logos in their t-shirts, phrases about California’s sunshine. It's after a moment that you realize there is something completely wrong with them. I respect this work I did at the time, but I don’t like it anymore. It was a part of my path ant it brought me where I am now. It helped me go through a really tough moment, but I learned how to treat the subject of war in a different, less harming way, at least for me.

After reading news for hours with tons of pictures of explosions, constantly worrying about my family, translating documentary movies for example about all the horrors we’ve found in reoccupied cities and painting dead bodies, I started having breakdowns, panic attacks, nightmares. I needed to find the way to work differently. These paintings helped me to understand how to develop the distance I needed.

I think good painting takes time. I’ve spent three months working on this canvas and I like where it's taking me, what I’m learning from it. In the future I will work faster, but I really enjoyed being trapped by the complexity of this transparent necklace, its mirror reflections and multiple dimensions in the same image. Each pearl hypnotized me and one by one I tried to find an end in its infinite depth, amazed by how true painting can be versus the tiring and tricky reality. By the way, I bought this necklace in an H&M store for 13 euros and it has transformed my artistic practice so much. This work helped me move on towards what I’m developing now.

Earlier I did a semi-abstract painting of an open-heart surgery, inspired by a painting by Luc Tuymans. You can hardly tell it's a heart, it looks more like a gem, but the heart is also right there. And you also see the heart in my necklace, here, in this modest object of kitsch. I’m developing a theme; still it has to do with the body, but differently.

Actually, in my practice I often refer to Luc Tuymans, because he also speaks about trauma in collective memory. His paintings often deal with difficult and controversial subjects, such as the Holocaust, political violence and racial discrimination, but are treated in a subtle and allusive manner. In my painting about an open-heart surgery, I refer to his work Eternity (2021) in which he deals with the explosion of the hydrogen bomb. I evoke his work in order to paint the state of uncertainty and vulnerability that we are going through in our own period of nuclear blackmail, when the risk of nuclear war is the greatest since World War II.

In other works, I zoom into the remains of our traumatic past and present. I review rushes from unedited documentaries about Ukraine that I have access to, and I stop at certain images that tell a common story. Like in images of the American or European clothes you see on children receiving aid with brands and phrases coming from very different places. Things that maybe were even manufactured in Ukraine but now come back as aid, all these objects that bear witness to the changes of the world and our changing position in it. All the meaningless objects of civilian life can become objects of war in an instant. What does it all mean? What should we do with it?

As for the future, I’m looking forward to the summer when I’d like to go on a residency elsewhere, maybe Mexico or Morocco, but most of all I want to go to Ukraine for a month at least. It’s my source of energy, when I’m home I finally have a feeling that I’m in a right place.

-

You can follow Viktoria Oreshko on Instagram.

+

You can watch a documentary made by the artist’s father on the Orange Revolution (Kyiv, 2004):

A documentary on the same period (from the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict):

And the short documentary The Fight for Ukraine: Last Days of the Revolution (from VICE):