Vasco Falcão: dessins et bois brûlés

On Vasco Falcão's first solo exhibition at the Centre Culturel Le CAP in Plérin.

Dear all,

We’ve given an entire turn around the sun since I inaugurated this newsletter with a text about ruangrupa’s documenta fifteen, followed by reflections on Jimmie Durham’s retrospective Humanity is not a completed project curated by Kathryn Weir, on the exhibition I curated, Chromosome Comic, and on a major exhibition of Tove Janssen, Houses of Tove curated by Sini Rinne-Kanto.

To celebrate, here is a text about Vasco Falcão, an artist I met this summer in Saint-Brieuc, a coastal town in Brittany where he lives and where he has his studio in what used to be the village butcher's shop, a place he is painstakingly restoring (you can see images of his studio on my instagram). In October, the artist opened Vasco Falcão: dessins et bois brûlés, his first solo exhibition, currently at the Centre Culturel Le CAP in Plérin. Sincere thanks to Swan for introducing him to us.

As ever, thank you for your reading time, feedback, suggestions and encouragement, it’s all deeply appreciated. I’ll see you again in January when we will visit the studio of Viktoria Oreshko.

Cheers!,

Marisol

-

Like apparitions or ghosts, the characters emerge in Vasco Falcão's burnt woods, drawings pyrographed with a technique that is unusual in its refinement, but also second to the artist's sensibility, powerfully present in the almost thirty pieces that make up his first solo exhibition, on view at the Centre Culturel Le CAP in Plérin.

The mostly pyrogravures on plywood panels, and some medium-format ballpoint pen drawings on paper, follow the Guinea-Bisseau-born artist's passage through Vienna, Puducherry, Paris and Saint-Brieuc, where he currently has his studio. The text in the exhibition is brief and tells us little more than these facts that make us imagine an artist on the move, perhaps struggling to find the place to pose the large and heavy supports of his art. Faced with these voids in an otherwise intriguing story, the artist insists on directing us to the work, urging us to see it, listen to it.

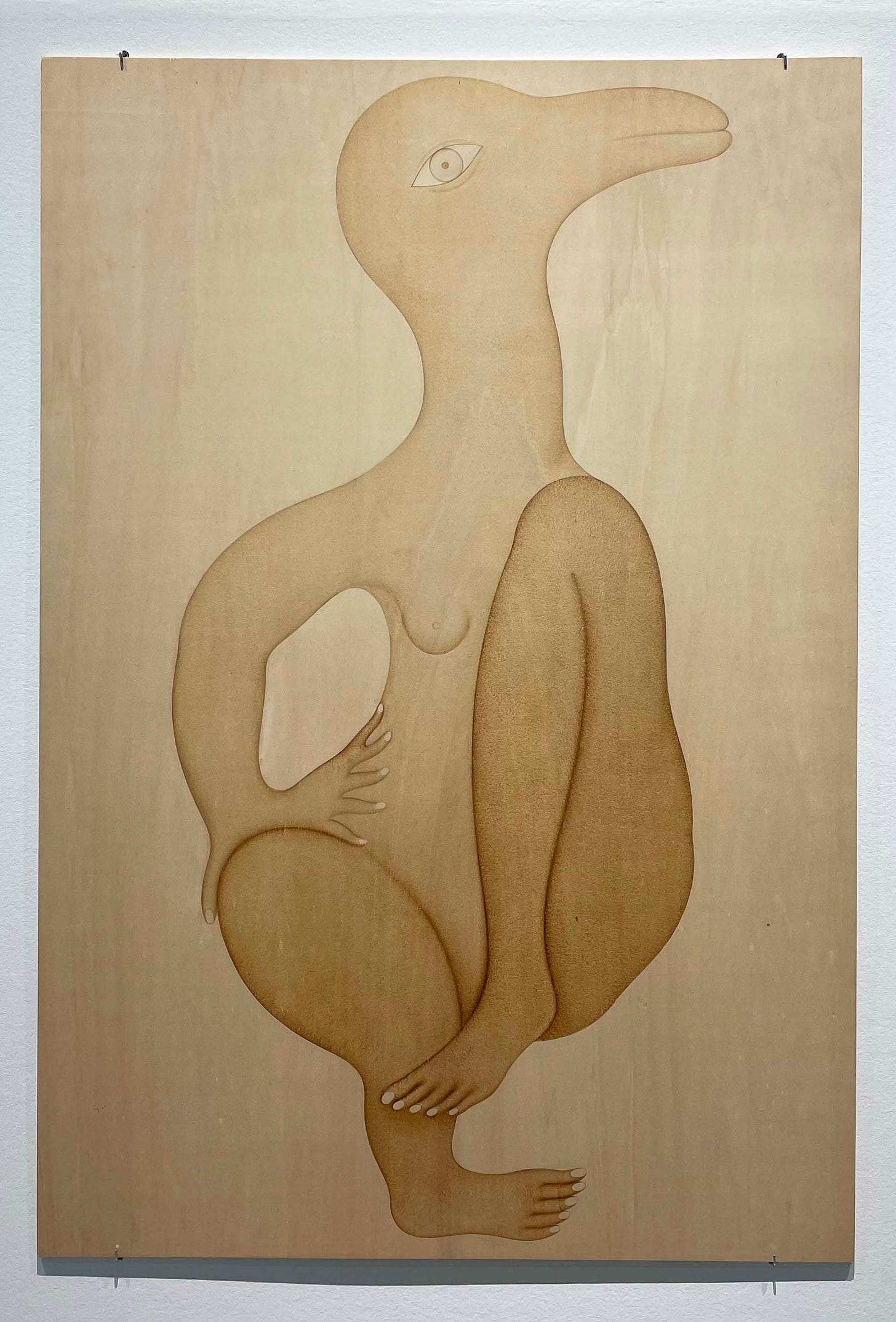

Indeed, the works greet us with emotional eloquence. In them, we find curves like the folds of a skin, like the contour of a bulging belly, or the silhouette of a breast in images that move in an ambiguous space, between voluptuousness and melancholy. These bodies merge with natural or abstract elements in subtle gestures, often highlighting the strokes of the wood, seemingly becoming the stripes of a zebra or the shape of flames trapped within the material.

At the entrance of the exhibition, six panels present variations inspired by the artist’s experiences and reflections during the COVID lockdowns. A series of bird-women move in different spaces, timidly protecting themselves, covering their nudity even as they try to stretch proudly or bend resignedly. The images underline the fragility of the vivid characters and the discomfort of the space around them, the mismatch between the captivity their bodies endure and the freedom they inherently need.

"The woman holds a central place in my culture, where the mother comes before God," explains the artist before delving into a diptych of drawings inspired by the story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman in the American South in the 19th century who chose to kill one of her daughters rather than surrender her back to the plantation they had briefly escaped from. The story, symbolic of the descent into hell represented by the Atlantic slave trade, haunts the artist (as it has haunted others, including Toni Morrison who wrote Beloved inspired by it) as he attempts to explore the depths of a pain capable of the unthinkable in order to avoid, and spare one's own, the abject humiliations of captivity.

Escape, or the impossibility of escaping, returns in an oeuvre that is both dense but delicately expressed, like a terrible secret that is revealed in a whisper. The artist's tool, a clunky pyrographer "that costs 14 euros in any hardware store", is a latent metaphor. The red-hot iron with which he draws are the facts - whether lived, historical or from the news - that obsess him, which he has to appease in order to sublimate them. The process, slow and physically intense as the work is the sum of an infinity of light microgestures, is a search to give form and voice to characters that, in the artists’ words, “already inhabit our world”.

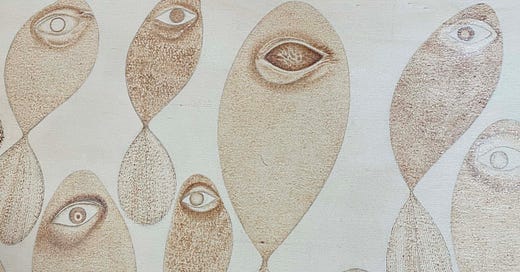

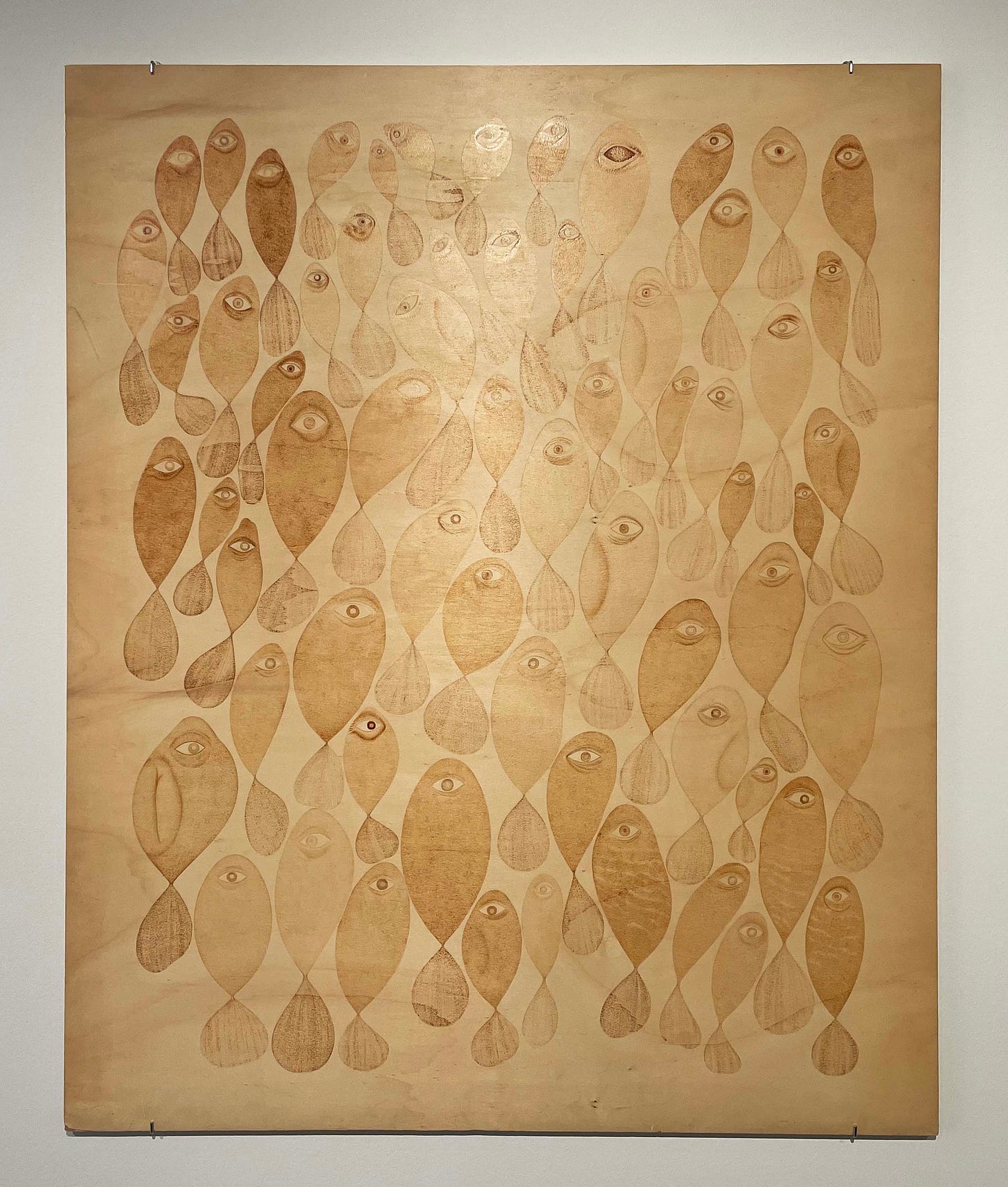

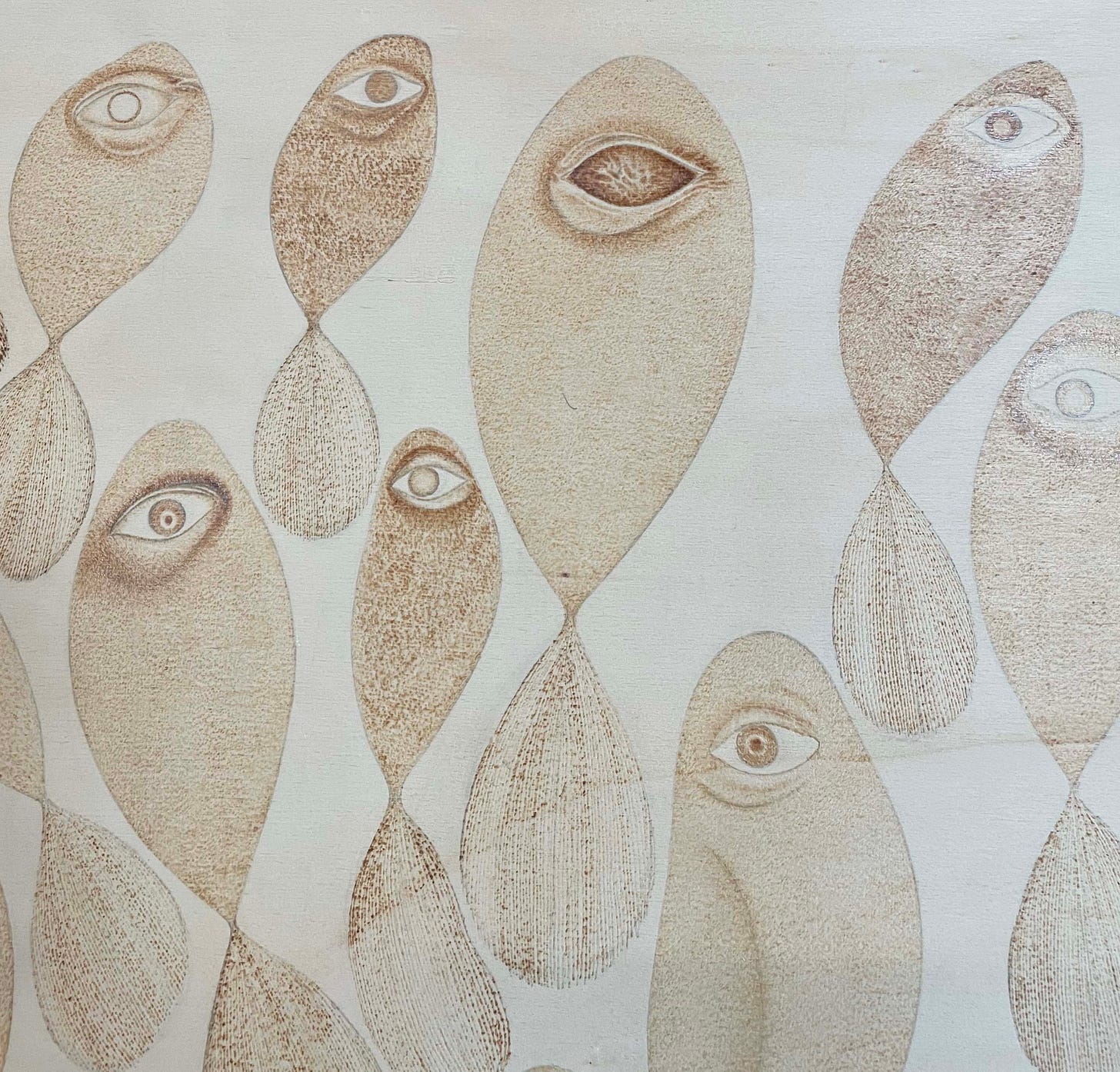

The creation of human-animal hybrid creatures allow him to express situations that are almost indescribable in their barbaric reality. For example, in an untitled piece, a school of fish of various sizes moves in apparent harmony in the often rectangular space, but after a moment we recognise in each one a cyclops watching us, observing our environment with a mix of surprise, weariness and horror. In each eye we discover a different personality and, invariably, a deep sorrow. It is not difficult to imagine that these beings represent the lives lost with banal regularity on the Mediterranean Sea.

In Vasco Falcão's work, we recognize reality pulsating in the background but also an almost eerie narrative force that speaks a universal language that goes beyond words.

Questioned on what his work is about during a recent visit of the exhibition by a group of locals, Falcão, a tall yet shy man, replied briefly in his native creole, explaining to me later that he had said his work was the expression of his desire for a society without violence, one in which women and children could be free, “when women and children suffer, you can be sure that all of society is suffering,” he added, implicitly including himself in the image.

Back in the work and with the artist’s guidance, we understand where this simple, yet apparently unattainable ambition in our societies might spring from. In the distance, a pyrogravure looks like a caricatured face with eyes, a mouth and a mouthlike orifice on the forehead. Shading suggests depth on each shape, at the center of which lay stick men figures with closed, open or empty eyes. The work is in fact the abstraction of an unpunished crime, an absurd political revenge committed against a group of children known to the artist in his native Bolama, a town filled up with ruins of buildings once belonging to the Portuguese colonial administration. Rendered with the ominous duality also found on Laylah Ali’s paintings or Kara Walker’s paper cuts, the work attracts you as it appears innocent and childlike only to disarm you with the reality that looms behind it.

The exhibition lighting produces an interesting, albeit unintended, effect: you sometimes have the impression of seeing an empty wooden panel and discovering the work on it as you approach it or move around it. Accidental or not, this effect is reminiscent of the artist's work, in that you move around it, first admiring the fluidity and lightness of his iron strokes, only to realise that you have been absorbed by the stories, tender or tragic, told by his spectral characters.

-

Vasco Falcão was born in Bolama, Guinea-Bissau in 1972. He lives and has his studio in Saint-Brieuc, Brittany.

-

Vasco Falcão: dessins et bois brūlés, is on view from October 20 - December 30, 2023 at the Centre Culturel Le CAP in Plérin.